What Was the Inca Empire (Tawantinsuyu)?

The Inca Empire was the largest state in pre-Columbian America. In Quechua it was called

Tawantinsuyu, “the four regions together.” I use Tawantinsuyu because, in my reading and in local

accounts I’ve collected, that name reflects how Incas saw their world: a union of quarters centered on Cusco. The state rose from a highland chiefdom to a continental power in barely a century,

integrating dozens of ethnic groups across the Andes through diplomacy, road building, and a disciplined labor system.

After comparing sources I keep coming back to the same idea: the Incas optimized for

control through infrastructure rather than markets or money. They did not mint coins. Instead they

mobilized labor, stored surplus in thousands of state warehouses, and moved people and goods across a spine of

engineered roads. The system worked because it tied local communities, or ayllus, to the state through

shared ritual, reciprocal obligations, and visible benefits like terraces and canals.

At its heart, Cusco was both sacred and administrative. From there, the Sapa Inca’s officials standardized measures,

rituals, and even clothing for state ceremonies, yet allowed regional variation where it kept peace. The empire ended

in the 1530s under Spanish conquest, but its administrative logic and cultural memory remain visible across the Andes.

Timeline and Peak in the 15th–16th Centuries

- c. 1200–1400: Formation of the Inca polity around Cusco.

- 1438–1471: Pachacuti expands and reorganizes the state.

- 1471–1493: Túpac Inca Yupanqui extends rule to the coast and north.

- 1493–1525: Huayna Cápac consolidates and reaches the apex.

- 1525–1532: Succession crisis and civil war between Huáscar and Atahualpa.

- 1532–1533: Spanish capture of Atahualpa and fall of Cusco.

From what I’ve studied, the apogee clearly sits in the 15th–16th centuries, when expansion,

architecture, and administration peaked.

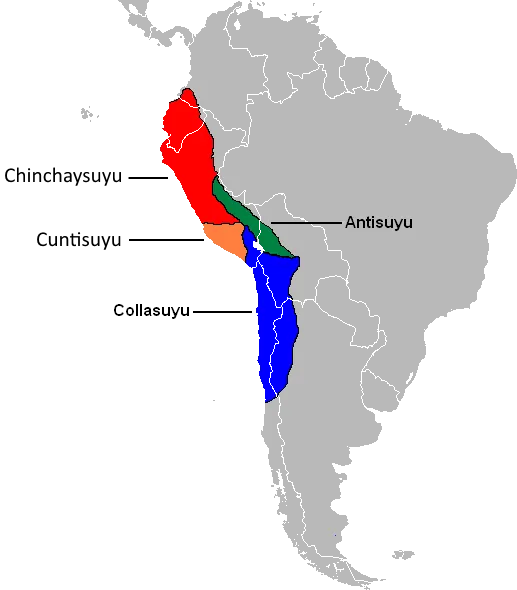

Capital Cusco and the Four Suyus

Cusco was laid out as a sacred landscape with major temples and palaces, radiating roads, and ceremonial plazas. The

empire’s quarters were:

- Chinchaysuyu (NW toward the coast and Ecuador)

- Antisuyu (NE toward the Amazon)

- Collasuyu (SE toward the Altiplano)

- Contisuyu (SW toward Arequipa and the coast)

In local stories I’ve heard, people still map identity to these directions, showing how geography and government

intertwined.

The 14 Inca Emperors at a Glance

Inca tradition remembers a line of rulers from Manco Cápac to Atahualpa. Dates vary in sources, but the sequence and signature actions are consistent: foundation, expansion, consolidation, crisis.

From Manco Cápac to Atahualpa

- Manco Cápac: legendary founder linked to the Sun.

- Sinchi Roca → Lloque Yupanqui → Mayta Cápac: early consolidation around Cusco.

- Cápac Yupanqui: first wider campaigns.

- Inca Roca: reorganizes nobility.

- Yáhuar Huaca: internal strife.

- Viracocha Inca: expansion begins; flees during Chanca threat.

- Pachacuti (1438–1471): state reengineer; stones of Cusco and Machu Picchu often linked to his reign.

- Túpac Inca Yupanqui (1471–1493): maritime and northern expansions.

- Huayna Cápac (1493–1525): apex; northern capital at Tumebamba.

- Huáscar vs Atahualpa: civil war; Atahualpa captured by Spaniards.

When I cross-checked emperor lists for this article, I focused on consistency of achievements rather

than exact dates, which tend to shift by source.

Quick Facts Table: Dates and Achievements

| Ruler | Approx. Dates | Signature Achievements |

|---|---|---|

| Pachacuti | 1438–1471 | State reform, major building program, imperial ideology |

| Túpac Inca Yupanqui | 1471–1493 | Northern and coastal expansion, naval ventures |

| Huayna Cápac | 1493–1525 | Peak territorial extent, administrative consolidation |

| Atahualpa | 1532–1533 | Civil war victor, captured by Spaniards |

How the Inca Empire Worked

Government and Social Structure (ayllu, curacas)

Society was organized in ayllus—kin-based communities with shared lands. Local leaders

(curacas) mediated between state and village. Above them stood provincial governors and royal

administrators who recorded obligations and censuses. From what I’ve learned in books and lectures, the state’s

genius was to embed administration inside kinship, making taxes feel like duties to community and

ruler at once.

Economy and Agriculture on Terraces

Agriculture relied on altitude zoning: maize in lower valleys, potatoes and quinoa higher up, camelid herding above.

Incas expanded this with andénes (stone terraces), canals, and frost-management strategies. I often

cite terraces as the clearest case where engineering met ecology: the design stabilized slopes, conserved water, and

increased yields.

Roads and Engineering: The Qhapaq Ñan

The Qhapaq Ñan was a continent-spanning road network with suspension bridges, causeways,

tambos (way stations), and guard posts. Messengers (chasquis) relayed information at speed. In local

accounts I’ve heard, some villages still mark old relay points, showing how infrastructure left social footprints,

not just stones.

Quipu: Record-Keeping Without Writing

The quipu was a system of knotted strings that tracked labor, census, and storehouse contents.

Colors, knot types, and positions encoded meaning. I didn’t witness quipu use, obviously, but the scholarship I’ve

read argues it functioned as administrative writing, even if it looked nothing like ink on paper.

Religion and Worldview

Main Deities: Inti, Viracocha, Pachamama

- Inti: patron of Cusco and royal lineage.

- Viracocha: creator god associated with ordering the world.

- Pachamama: earth/time, honored in sowing and harvest rites.

Rituals, Cosmology, and Symbols

Key rituals included Capac Hucha (state ceremonies), offerings at huacas (sacred

places), and seasonal feasts. Iconography favored solar disks, puma and condor motifs, and fine textiles that signaled

rank.

The Fall and What Remains

Civil War and Spanish Conquest

- Epidemic and succession disputes weakened central control.

- Spanish troops arrived with steel, horses, firearms, and local allies.

- The administrative core collapsed, but many communities survived by reshaping older institutions.

Legacy Today in the Andes

You still see Tawantinsuyu in place-names, ritual calendars, foods, and the logic of communal work. Museums and

archaeological parks preserve sites, while local festivals keep cosmology in motion.